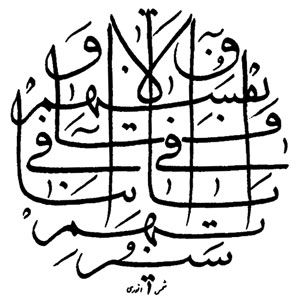

Oneness

In the Beshara translation of ‘Kernel of the Kernel‘, the great Andalusian Sufi Ibn Arabi writes: “It is essential to know that as there is no end to the Ipseity [Selfhood] of God or to His qualification, consequently the Universes have no end or number, because the Universes are the places of manifestation for the Names and Qualities. As that which manifests is endless, so the places of manifestation must be endless. Consequently, the Quranic sentence: “He is at every moment in a different configuration,” (Q55:29) means equally that there is no end to the revelation of God.” (ch. 3, p10) Alternative translations suggest that Allah is always in a different “work” rather than “configuration”.

Anyway, the point is that Beshara emphasises the Oneness of the universe with God. For Beshara, God is the substance of the universe. Everything we experience is God Himself in a different configuration. I would like to explore this idea, and contrast it with what I perceive to be the more orthodox Islamic interpretation that the Creator is separate from His creation. What does this imply about reality, about substance? If only God is Real, then anything other than God must be illusory. Does this mean that the creation is illusory? If we consider that “everything is perishing but His Face” (Q28:88) then this surely confirms that only God is Real, and that everything else, being impermanent, is illusory?

In ‘Kernel of the Kernel’ Ibn Arabi describes ‘five presences’ (ch 3), saying that all “these [myriad] universes are encompassed by the five presences”. The first presence is a station of God in which “no qualification or name is possible . . . Whatever word is used to explain this station is inadequate because at this Presence the Ipseity [selfhood] of God is in Complete Transcendence from everything, because He has not yet descended into the Circle of Names and Qualities. All the Names and Qualities are buried in annihilation in the Ipseity of God”. This station of Transcendence is how we think of God prior to creation. Moreover “When Hazreti ‘Ali heard the Hadith “At that time God was in a state such that there was nothing with Him.” he added, “Even at this moment He is still so.”” (ch 3). So Ali seems to be advancing the orthodox Islamic view of God as Transcending the creation.

The subsequent presences are the creation, starting with the reality of Muhammad (2nd presence), the degree of the angels (3rd presence), the universe of galaxies (4th presence), ending with the perfect man (5th presence). Orthodox Islam would consider these separate from God, but Beshara considers them One with God. One Beshara friend used the analogy of water: the 1st presence is described as “the Ocean-Deep point” and the subsequent presences are Rivers and Tributaries flowing from this Ocean. According to this view, all the Presences have the same Substance: God.

This Beshara view clearly emphasises immanence over transcendence. The strength of this view is that the mystical experience is one of closeness to God within His creation — the sense of immanence. However, I suggest that we can happily explain the creation as a series of signs pointing to God and the mystic as an adept sign-reader, so that there is no need to posit God as the Substance of creation. In fact, because the creation is illusory it has no substance, in my view.

When I say that created things are illusory, the best comparison is a rainbow. A rainbow is an appearance that depends on causes and conditions: if the necessary causes and conditions such as sunshine and rain are gathered then a rainbow appears. All created things are like this: each depends on its specific causes and conditions, and the Primary Cause is God. If any necessary cause or condition is absent then the thing does not come into creation. Because every thing is impermanent, sooner or later one of its sustaining causes will cease and the thing will disappear. This is why everything is illusory.

Another way of expressing the same idea is to say that created things lack essence. For example, if we look at a coffee table and we try to find its essence — the coffee table ‘in itself’ — we will not be able to find it. We might try to find this essence in the table legs or the table top, but we will not succeed. However, if we are satisfied with the mere appearance of the coffee table then it will function perfectly well for us: we can put books and magazines on it. By saying that things are illusory I am not saying that they don’t function. We may dream about driving a car, and the dream car may function perfectly as a car, but when we wake up we realise it was an illusion.

These lines of reasoning come from the Buddhist tradition, but I believe they are universally valid. When God finished the Quran by saying “This day I have perfected your religion” (Q5:3) He did not negate all the truths of previous religions. I believe that Islam contains or is compatible with all the key truths of the previous great religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, Christianity and Judaism.

One of Buddhism’s key strengths is its path of negation (via negativa), its philosophical reasoning that challenges our sense of what is fixed and strips away illusion, leaving . . . emptiness. This emptiness is a negative phenomenon (a lack or void) without positive qualities or attributes — we cannot say (predicate) anything true about emptiness. As emptiness is the ultimate truth taught by the Buddha he could not describe himself as a Prophet — how can there be a Prophet of emptiness?

Nevertheless, the Buddhist path of negation is consistent with the theological via negativa of Thomas Aquinas and Maimonides, who both realised that it is impossible to say anything ultimately true about God. We can say what God isn’t (He isn’t a coffee table), but ultimately we cannot say what God is. This is the truth of Ibn Arabi’s first presence: “No qualification or name is possible at this station. Whatever word is used to explain this station is inadequate”. (ch 3)

So, created things are illusory because they arise in dependence upon their causes (including God), their parts and their names. Nevertheless, we do not normally relate to things as illusory. in fact we often grasp at created things as permanent, having fixed essence or self, as independent, and existing from their own side. According to Buddhism this self-grasping ignorance is the origin of suffering and the engine of samsara / maya.

From a Sufi point of view, if we use the example of our self, we see that our mistaken view of our self as independent from God, as existing from its own side, is the ignorance which obscures / prevents gnosis. Only if this false view of self is annihilated (fana) by God can we come to know God. We can see clearly that God is not one with the false self which we perceive in ignorance.

This same reasoning applies to all our other mistaken perceptions: insofar as I perceive trees, cars, tables etc as existing independently of God then I am mistaken – I am perceiving things that don’t really exist – I am trapped in maya. However, if I negate my mistaken perceptions, and come to see the trees, cars and tables as depending on God, then my awareness is correct.

The problem with oneness is that it is tempting to apply it to the things I normally see, which are false. It is necessary to negate these things first, to annihilate them in God. Only once they have been annihilated can they arise again (baqa) in Truth. At this point it is meaningful to describe them as One with God. But if we prematurely apply oneness to the false things that appear to the mistaken mind prior to annihilation, we will create a barrier between ourselves and God. (May Allah guide and protect us all.)

In his book “Indian Philosophy” (p215), Richard King succinctly explains the concept of oneness according to Advaita-Vedanta. Taking the word Brahman as meaning God, the passage supports your view of the world as unreal if seen as independent of God, but real if seen as dependent. The passage also seems to support my view that we must negate the unreal before we can perceive the real.

“[The great Advaita-Vedanta philosopher] Sankara makes three major statements:

1. Brahman is real

2. The universe is unreal

3. The universe is Brahman

“The third statement is meant to explain the significance of the first two. The world is unreal as such, that is, as the world, but it is real in so far as it is seen as non-different from Brahman – the ground of existence. Clearly Sankara does not wish to imply that the world is absolutely unreal in the sense of being without any basis in reality. As he states in his famous commentary on the Brahma Sutra: “As the space within pots or jars are non-different from the cosmic space or as water in a mirage is non-different from a (sandy) desert . . . even so it is to be understood that this diverse phenomenal world of experiences, things experienced, and so on, has no existence apart from Brahman.” The world cannot be completely unreal then since it is a manifestation of Brahman. However, at the same time the world is not real in the same sense as Brahman, that is, from the level of ultimate truth, because it is subject to change. Only Brahman is real in this ultimate sense. Implicitly then, one can talk of three levels: [1] the unreal or delusory, [2] that which is real on a practical or empirical level and [3] ultimate reality.”

The challenge, as I see it, is to strip away the mistaken appearance of independence from practical [level 2] phenomena. In Buddhism this mistaken appearance is known as ‘dualistic appearance’ because practical truths normally appear mixed with a mistaken appearance of independence. They must undergo a process of experiential negation / deconstruction / annihilation before they can they appear unmistakenly as mere practical truths, mere dependent arisings.

At What Point Does the Gap Close Between God and Man?

The concepts of Divine transcendence and immanence describe humanity’s relationship with God. They can be simplified to separation and proximity.

Listen to this reed as it is grieving; it tells the story of our separations.

“Since I was severed from the bed of reeds, in my cry men and women have lamented.

I need the breast that’s torn to shreds by parting to give expression to the pain of heartache.

Whoever finds himself left far from home looks forward to the day of his reunion.”

These are the opening lines of Rumi’s spiritual epic, the Masnavi (trans. Williams 2006). Indeed, separation / transcendence is the starting point for much theology. Yet Divine proximity / immanence is also key. In the Quran, God says of His relationship with man:

“We are nearer to him than his jugular vein” (Q50:16).

How can God be both separate from and close to us, transcendent and immanent? The relationship or distance between a person and God is not fixed. In a Hadith Qudsi, God says:

“Take one step towards me, I will take ten steps towards you.

Walk towards me, I will run towards you.”

If we take this to its extreme, at what point does the gap close between God and man? If we continue taking steps towards God and God continues running towards us, do we ever meet or, as Rumi suggests, achieve ‘reunion’? Some Sufi mystics such as Bayazid Bistami and Mansur Al-Hallaj have achieved states of union with the Divine, and the question “Who was greater, Muhammad the Prophet or Bayazid Bistami?” caused Rumi to swoon on his first encounter with his mystical initiator Shamsuddin.

“While the Prophet said: ‘We do not know Thee as it behoves!’, the Sufi Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī called out: ‘Subḥanī’, ‘Praise to me!’ If we are to believe legend, it was the contrast between these two utterances that awakened Mawlānā Rūmī to the spiritual life. Rūmī, so it is told, fainted when listening to Shams’s shocking question about whether Bāyezīd or the Prophet was greater, a question based on the two men’s respective sayings that express the human reactions to the meeting with the Divine. The tensions between the two poles of religious experience, that of the prophet, who knows his role as humble ‘servant’, and that of the mystic, who loses himself in loving union, became clear to him.” Annemarie Schimmel, ‘Deciphering The Signs Of God’ (Gifford Lecture)

Sufi Wisdom

“Love all and hate none.

Mere talk of peace will avail you naught.

Mere talk of God and religion will not take you far.

Bring out all the latent powers of your being and reveal the full magnificence of your immortal self.

Be overflowing with peace and joy, and scatter them wherever you are and wherever you go.

Be a blazing fire of truth, be a beauteous blossom of love and be a soothing balm of peace.

With your spiritual light, dispel the darkness of ignorance;

dissolve the clouds of discord and war and spread goodwill, peace, and harmony among the people.

Never seek any help, charity, or favors from anybody except God.

Never go the court of kings, but never refuse to bless and help the needy and the poor, the widow, and the orphan, if they come to your door.

This is your mission, to serve the people…..

Carry it out dutifully and courageously, so that I, as your Pir-o-Murshid, may not be ashamed of any shortcomings on your part before the Almighty God and our holy predecessors in the Sufi order (silsila) on the Day of Judgment.”

This was final discourse of Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti (1141-1230CE) to his disciples, one month before his death.

The Beautiful Irony

A valid comparison can be drawn between money addicts and heroin addicts. Neither group can be trusted, but it is not appropriate to hate either heroin or money addicts because they are both sick. Addicts shouldn’t be allowed to run our industries or invest our money but we shouldn’t hate them. They are not in control of their own behaviour – they are not themselves. Not being themselves, they are incapable of experiencing empathy and compassion. The beautiful irony is that the self is entirely unselfish when it is at its healthiest. Only the diseased self, full of fear and insecurity, grasps onto what it perceives as “mine” at the expense of other people.

Elite education can drive out co-operative instincts like empathy and compassion. However I don’t think this is inevitable, and I believe it is possible to learn techniques of intellectual and emotional self-defence to protect against this brutalising effect. These techniques are widely applicable because, as George Monbiot points out (1), in modern society we are besieged by advertisements trying to undermine our healthy, intrinsic self-worth. Through causing alienation, corporations seek to refocus our self-esteem around their superficial products and brands, and delude us into pointless competition against each other.

Fitra is the Islamic concept of the underlying purity of the self. Fitra means ‘pure primordial nature’ or ‘basic goodness’ and is an Arabic word appearing in the Qur’an. The Prophet Muhammad (saws) said that every child is born with perfect fitra (1). Subsequent human impurities are ‘adventitious’, i.e. they arise due to upbringing, circumstance etc. Muslims believe that Islam is the religion which perfectly expresses this pure primordial nature because fitra is naturally drawn to the One God, to Whom the Muslim monotheistic practice of tawhid is the best path.

In his essay ‘Fitra: An Islamic Model for Humans and the Environment’ (2) the Sufi scholar and leader Saadia Khawar Khan Chishti discusses the relationship between fitra and care for the environment. He argues that spiritually healthy people (whose fitra is being well expressed) will naturally care for the environment and other people. For example, they will naturally be contented and will not require large quantities of consumer goods. He therefore argues that the solution to the environmental crisis must have a spiritual element – namely the clearing away of obstructions to fitra. Non-spiritual solutions on their own will not suffice.

The concept of fitra is similar to the concept of ‘Buddha nature’, which is also described as our natural, primordial purity. Buddhists believe in the interdependence of all life, and say that our Buddha nature is best expressed when we break down the egotistical barriers that falsely separate us from others. Therefore they say that “compassion is our Buddha nature” because, without a false ego and a diseased sense of self, like the Buddha we will naturally empathise with the suffering of others and want to relieve it.

***

1. George Monbiot, The Values of Everything (http://www.monbiot.com/archives/2010/10/11/the-values-of-everything/)

2. Sahih al-Bukhari, Volume 2, Book 23, Number 441. “No child is born except in al-fitra and then his parents make him Jewish, Christian or Magian (Zoroastrian), as an animal produces a perfect young animal: do you see any part of its body amputated?”

The Fetishisation Of The Market

Regarding public good vs business good, Anna Minton’s book ‘Ground Control’ describes how the urban planning process has been distorted in recent years in favour of business and against the public interest. Large sections of our cities (e.g. Liverpool 1) have now been privatised in order to provide lucrative shopping environments. Undesirables (e.g. young people, old people, homeless people) are excluded through various means, such as the ASBO.

The fetishisation of the private sector knows no bounds. The current Neoliberal Party government is being warned that withdrawing investment from the public sector too quickly will deepen the recession, because the private sector is not ready to take up the slack. One reason for this is because the banks are failing to lend. The proposed solution is more ‘quantitative easing’ – increasing the money supply so that the banks have more money to lend. But the evidence so far shows that banks use any additional money in the system to fatten their own balance sheets and pay bonuses, not to lend, no matter how many times Vince Cable ticks them off.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to miss out the middle-man? If the Bank of England has money to pump into the system, the best way to bring us out of recession is to invest directly in public infrastructure projects such as schools, hospitals, and public transport. The banks don’t need to stand in the middle, taking a cut through interest payments. This model of investment is different from PFI, the Neoliberal Party’s preferred mode of infrastructure ‘investment’ since the time of John Major, but why should the private sector sit in the middle of transactions between the government and the people, syphoning off our wealth and adding no value? The banking system in this country is just an organised form of corruption, and the government is entirely complicit.

The Moral Economy

Opposition to neo-liberalism can be summarised under the heading ‘the moral economy’. In a moral economy, human beings accept moral responsibility for what happens in the economy. We stop pretending that if everyone pursues their own selfish interest an ‘invisible hand’ is going to magically bring about our collective good.

Accepting moral responsibility does not entail taking control of every aspect of the economy. We can accept that, in some areas, properly regulated markets work reasonably well. However, the provision of universal public services should not be left to the market but should be performed by the public sector. Natural resources such as oil and metals belong to us all, and should not be left to small cabals to exploit and profiteer. We need to consume only as much oil as we need to create new renewable energy systems – the rest should be left in the ground if we want to have a future.

In a moral economy we should not be afraid to make qualitative as well as quantitative judgments: just because gambling and pornography are lucrative doesn’t mean they are useful parts of the economy. There needs to be clear understanding of the relationship between business good and public good: there are areas where they overlap and areas where they are mutually exclusive. Where business goes against the public interest it should be discouraged through regulation and taxation, and in some cases banned.

Manipulative technologies such as genetic modification are too dangerous to be left in the private sector. The trivial profit motive should not be involved in decisions which affect thousands of future generations. Harvesting and enclosing genes through patents is something that the public can have no truck with – how can it ever be in our interest? Amartya Sen’s research shows that small-scale farming by peasants is the most productive use of land and resources. We can feed the world with land reform, micro-finance and education. Genetic modification is an unnecessary, greedy innovation.

Babylon Must Fall

Neo-liberalism is an ideological blind faith in markets. Like all dogmas or pseudo-sciences, its adherents continue to grasp at it, regardless of how many facts and events prove that markets do not work. They endlessly chant the mantra “public bad, private good”.

As Derek Wall discusses in his book ‘Beyond Babylon’ there is a range of alternatives to neo-liberalism, ranging through Keynesian, regulatory, localist, eco-feminist, socialist and anarchist approaches, to name a few. They all have positive contributions to make, and all of us need to unite to slay the neo-liberal dragon.

I watched Ken Loach debate with Michael Heseltine on Newsnight last night. Loach attacked the Thatcher government’s record on unemployment and Hezza retorted that unemployment had also been high under Labour. Loach said that he should not be associated with the Blair and Brown government, but the exchange showed how the current political system hinges on the pretence that different factions within the Neoliberal Party offer genuine choice. The message is that once you have tried another faction (to no effect) you may as well lie back and let the Tories shaft you – which is where the British public is currently at.

Unless the Greens clearly articulate the message that we oppose the single Neoliberal Party with its blue, orange and red livery we will always be squeezed at general elections. Last time the political establishment was able to trick the voters that the orange faction offered some change, next time it will be the red faction etc etc ad infinitum (but Babylon must fall!).

Varieties Of Liberation Theology

Liberation Theology is normally associated with Latin American Catholicism. However, it can be understood as a radical tendency existing within all the major world religions, which each contain currents emphasising the following themes:

* working with the poor

* challenging authority

* seeking liberation in this life as well as the next

* favouring activism over contemplation

CHRISTIANITY

Liberation theology focuses on the needs of the poor and, in their interest, is prepared to challenge political and ecclesiastical hierarchies. In Latin America, the prototype was Bartolomé De Las Casas (1484 – 1566), a Dominican priest who became Bishop of Chiapas (the area which in recent times gave birth to the Zapatista movement). Against the grain of Spanish colonialism, De Las Casas envisioned a just society where indigenous people would co-exist peacefully and freely with the colonists instead of as slaves.

In the 20th Century, an important figure was Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador, assasinated in 1980. Previously a conservative, Romero inclined to liberation theology after a Jesuit colleague was killed for creating self-reliant groups among poor peasants. When the government refused to investigate, Romero spoke out against poverty, social injustice, assasinations and torture, until the death squads killed him too.

HINDUISM

Within Hinduism, Gandhi pioneered liberation theology. He successfully challenged the colonial power, and he also challenged the orthodox Hindu authorities, particularly with regard to untouchability, which led to his assasination by a Hindu extremist in 1948. Gandhi practiced karma yoga, the path to liberation through work, which in his case meant social and political activism. Gandhi combined the traditional Indian ideal of non-violence (ahimsa) with the Christian ideal of active love, to produce satyagraha, the theory and practice of non-violent direct action. Later, satyagraha was successfully adopted by Martin Luther King, another major figure in the history of liberation theology.

ISLAM

Sheikh Amadou Bamba of Senegal (1853 – 1927) offers a great example of liberation theology in an Islamic context. Founder of the Mouride Sufi movement, Bamba led a non-violent struggle against French colonialism. The French exiled and tortured him, which only strengthened his movement. Notably, Bamba emphasised work as a spiritual practice, and his followers are renowned for their industriousness, being involved in many economic enterprises throughout Senegal, such as groundnut cultivation.

BUDDHISM

In Sri Lanka the Sarvodaya Shramadana movement uses traditional Buddhist teachings such as the Four Noble Truths and the Wheel of Life to improve worldly conditions such as sanitation and food cultivation.

Reflections On Satyagraha

Activating our soul isn’t easy, and finding a way to change the world through soul-power (God we need it) can be even harder. This is the meaning of Satyagraha, the term first introduced by Mahatma Gandhi to describe his campaign in South Africa, now made into an opera by Philip Glass. Satyagraha the opera places Gandhi’s life in a mythological context, showing how Gandhi was first inspired by the Bhagavad Gita and the figures of Tagore and Tolstoy, and how he in turn came to be an inspiration to others, notably Martin Luther King.

At the start of the opera we see Gandhi inhabiting the mythical battlefield between the Pandava and Kaurava clans, together with the hero Arjuna and the god Krishna. Just as Arjuna is caught between the competing claims of the two clans, towards both of whom he feels loyalty, so Gandhi is caught between the rival claims of the British empire and the Indian people, towards both of who he feels loyalty. Just as Arjuna’s soul (Atman) is activated by Krishna’s wise counsel that he must have the courage to do his duty in the face of life’s conflicts, so too is Gandhi’s. The scene ends with the solemn vow of Brahmacarya, as Gandhi / Arjuna promises to dedicate his life to courageous service.

Mobilising the soul as an active force in human politics and the affairs of the world is no easy task, and Gandhi draws hostility, ridicule and even violence upon himself as he adopts the dress and lifestyle of a renunciate. Yet the ways of the spirit are subtle, and profoundly affect the human sphere through what appear, on the surface, to be simple acts, but which are imbued with great symbolism and resonance. We see this played out as Gandhi and his followers burn their identity cards (‘passes’) to protest against the racist laws of the time. This simple act is incredibly liberating, both spiritually and politically, and lifts them to a new plane of existence.

Satyagraha is ‘the surgery of the soul’, because it is a method for bringing about a profound change of heart in ourselves and others which leads to political and social change. The Satyagrahi must be courageous and willing to sacrifice his or her own well-being in order to demonstrate truth. It is only the courageous demonstration of truth that can touch the soul of the oppressor, and cause him to change or at least relent. This, finally, is the meaning of Satyagraha – that profound, long-lasting change, whether personal or political, must originate from within, and the only method that ultimately works is one based on understanding and harnessing the soul.

The Sufi Path of Service

How can we distinguish between fatal and liberating choices? That was the question posed this week by Sheikh Aly N’Daw, head of the International Sufi School. He was speaking at his book launch in Westminster, which was hosted by Ian Stewart MP, chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Friends of Islam group. Aly N’Daw is from the Mouride school of Sufism founded by the Senegalese saint Amadou Bamba (1850-1927) who emphasised service to others as the path to God. Sheikh Aly encourages his students to study the lives of great men and women who have bridged the gap between politics and spirituality, and have demonstrated how peace within leads to peace in the world.

Sheikh Aly asked us to consider the choice that Martin Luther King made when he decided not to opt for a comfortable lifestyle in Chicago, but to take his ministry to the South and confront the spectre of racial discrimination. On the surface, it appears that Dr. King made a fatal choice, because his ministry ended with his assasination. However, in reality he made a liberating choice, because he could have suffered spiritual death by taking the easy option of remaining in Chicago, and his sacrifice contributed to the political and social liberation of millions of African-Americans.

Next we were asked to consider Muhammad Yunus, pioneer of micro-credit and founder of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. A professor of economics, he became disillusioned with academic life and went to live with a group of peasants. Many people would consider this a fatal choice, at least professionally, but for Muhammad Yunus it was liberating because it showed him how small sums of money loaned on trust could yield massive results if targetted at the right people, particularly women. By 2008 the Grameen Bank had loaned US$7.8 billion to the poor.

Ian Stewart MP talked about his own difficult choice, to vote for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He explained that his motivation had been to help the Kurds and the Marsh Arabs, but now that hundreds of thousands of people had died as a result of the war, he could not be sure if he had been right. He described the whirl of conventional political life and how politicians, caught in the maelstrom, are on auto-pilot, without time or space to connect with the spiritual dimension of life. As he is not standing in the forthcoming general election, he expressed the hope that he would now have time to learn more about what Sufism describes as the spiritual heart.

The first two books in Sheikh Aly N’Daw’s series are ‘The Initiatory Way To Peace’ and ‘Liberation Therapy’. If you would like to buy a copy, please email: contact_uk@international-sufi-school.org . The International Sufi School’s next event is a conference in Edinburgh in May entitled ‘Nonviolence Within: Peace For All’ (http://www.nonviolence-edinburgh.com/)